Lucia WIlcox American, 1902-1974

Lucia Wilcox (1902-1974) born Lucia Anavi in Beirut, Lebanon, was a pioneering figure in the world of 20th-century art. Her life and work reflect a deep passion for creativity and resilience in the face of adversity. Born to a French mother and a Lebanese father, Lucia's early years were marked by a cultural richness that would later inform her artistic vision. At the age of 14, driven by a fervent desire to pursue her artistic ambitions, Lucia ran away from home and moved to Paris. In the vibrant art scene of Paris, she found herself surrounded by some of the most influential artists of the time. She frequented the Café de Flore on Boulevard St. Germain, where she met Fernand Léger, Pablo Picasso, and Piet Mondrian. These encounters played a crucial role in shaping her artistic path.

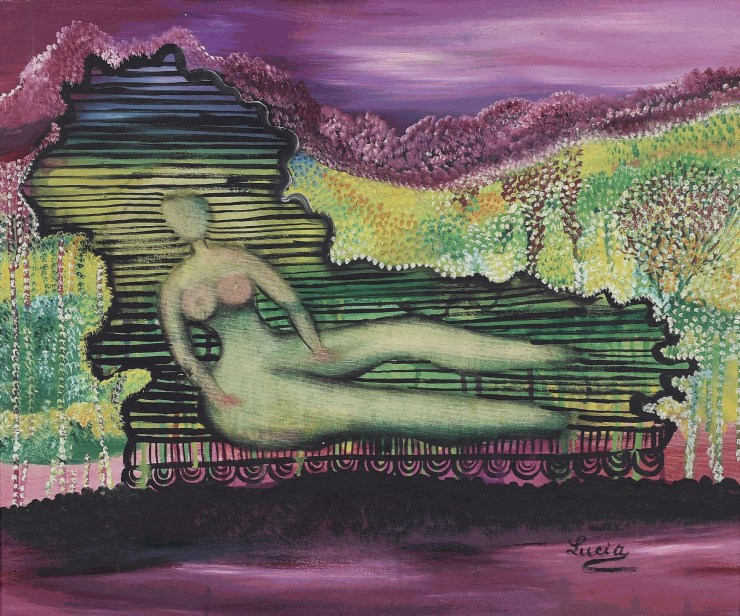

Despite the challenges of being a young, aspiring artist in Paris, Lucia's determination led her to enroll at the Académie Ronsart, where she honed her skills. Her relationships within the art community continued to expand, and she was soon taken under the wing of noted artist André Derain, who introduced her to exhibitions and encouraged her development as a painter. Lucia's first marriage, which she preferred not to discuss, ended in separation. However, her personal life took a positive turn when she met and married the Italian painter Francesco Cristofanetti. The couple spent 14 years together, during which Lucia's artistic career began to flourish.

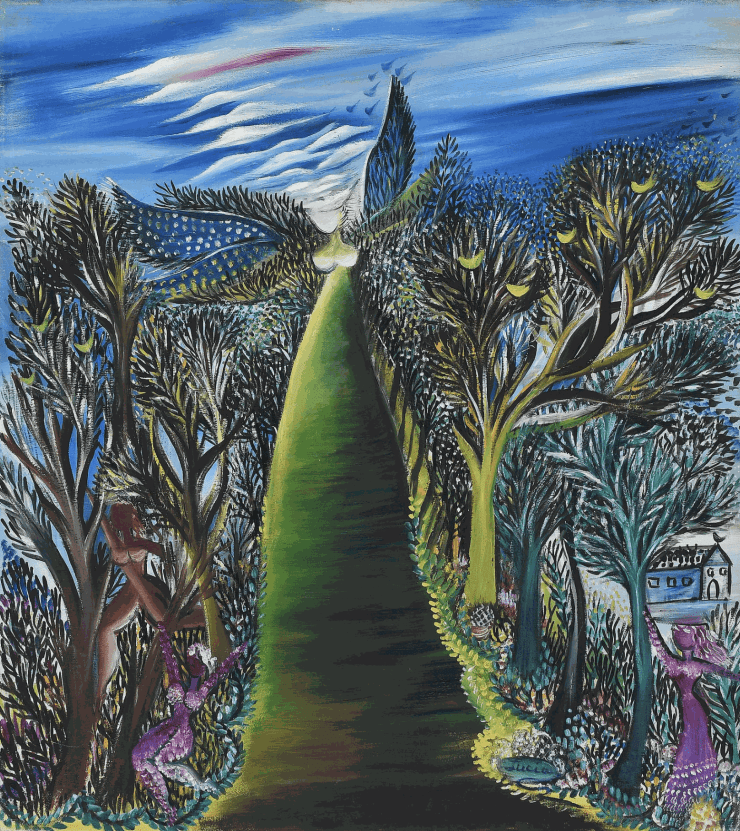

Her work caught the attention of the wealthy American expatriates Gerald and Sara Murphy, who were prominent patrons of the arts. The Murphy’s played a pivotal role in Lucia's life by sponsoring her move to the United States in 1938, where she became a fixture in the East Hampton art community. She had little money, but she did own a painting by Utrillo. After selling that painting, in 1946, she bought a rambling, deteriorating house on Abraham’s Path in Amagansett, East Hampton. Around this time Anai's Nin stayed with Lucia, Anaïs writing a book in which Lucia is a leading character. She marries Roger Wilcox, a painter and inventor, and together they renovate a big old house, turning it into not just a home but also a gallery and a place to host weekly barbeques through the summer season. At those barbeques and in picnics Lucia would make Syrian-style picnics for her husband, Roger, and Pollock to take to the beach. They would clam for hours, while enjoying her stuffed grape leaves, hummus, and baba ghanoush. Artists such as Frederick Kiesler, Max Ernst, Willem de Kooning, James Brooks, and many others enjoyed her culinary talents learned in Lebanon and refined in Paris in those days.

Her first solo exhibition was held at the prestigious Sidney Janis Gallery in New York in 1948, marking her entry into the American art world. Over the years, her work was also exhibited at the Lefebre Gallery and in various group shows, cementing her reputation as a significant contributor to abstract expressionism.

Lucia's art was known for its fluidity and abstract forms, though she resisted being labeled within any specific artistic movement. Her work, characterized by bold lines and dynamic compositions, often reflected her inner emotional landscape. She believed that art should not be confined to rigid classifications but should be a free expression of the artist's vision.

Tragedy struck in 1972, three months after her 70th birthday, Wilcox, , went blind as a result of an epithelial carcinoma in her nasal cavity. She spent 13 weeks in the Neurological Institute at Columbia‐Presbyterian Hospital in New York undergoing intensive radiation therapy for her inoperable tumor.

Almost every morning, Mrs. Wilcox, guided by her husband, Roger, sat down in the living room of their spacious, art‐filled frame house here, resting a pad of artists' heavy pater on her lap, uncaps a felt‐tipped pen, and, out of the fantasies she can visualize only in her mind's eye, creating a sketch.

Many of them display remarkable symmetry and have graceful, flowing lines and the élan of youth. The only guide she used was her hand, which tells her, when she begins her drawing, how far the pen's tip is from the edge of the paper.

“When I realized that I was blind,” Mrs. Wilcox said recently, “I decided I did not want to become a second‐class citizen. Nor did I want to lament my condition and feel sorry for myself.

“I said to myself, you now have to live with your blindness, and you should continue to create. So, I fought for being the person I was, only using a pen instead of oils and colors.”

“It's all magic,” Mrs. Wilcox said. “It's play fantasy that I put on paper, and the picture must have motion. I do it very fast, and I am very tense, for if I should forget my

conception I might leave out a leg or an arm. And, as you can see by looking at one of my inks, it's all one line.”

Drawing blind is something that sighted artists occasionally do. Among those who have experimented with the technique, which calls for a blindfold and no peeking, is Willem De Kooning, Mrs. Wilcox's good friend who lives in nearby Springs. Five years ago, in fact, Mr. De Kooning did a charcoal portrait of Mrs. Wilcox while blindfolded and gave it to her as a present.

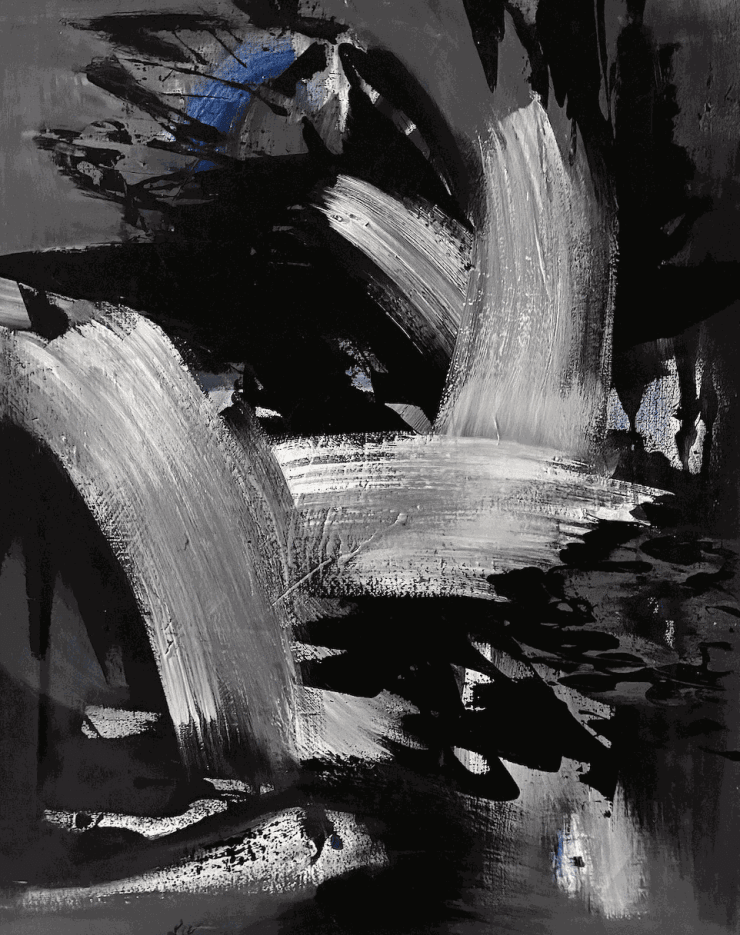

Her final exhibition in 1974 at the Castelli Gallery marked a significant moment in both her personal journey and the broader art world. By then, Wilcox was a well-established figure, known for her contributions to the Amagansett artists' colony and her influential role in shaping the postwar art scene. However, this exhibition held particular significance because it was one of the first major showcases of her work created after she lost her sight..

The 1974 exhibition at the Castelli Gallery was a powerful testament to Wilcox’s resilience and artistic vision. The gallery, renowned for its association with some of the most influential artists of the 20th century, provided the perfect venue for Wilcox’s first major show after her blindness. It was a place where innovation and creativity were celebrated, making it a fitting stage for Wilcox's new body of work.

The drawings and ink sketches presented in this exhibition were unlike anything Wilcox had produced before. Relying solely on her sense of touch and the images she could visualize in her mind’s eye; she created works that were both intricate and emotionally charged. The pieces displayed a remarkable symmetry and a fluidity of line that belied the fact that they were created by someone who could no longer see. Her use of a felt-tipped pen allowed her to explore the textures and movements of ink in ways that had not been possible in her earlier, more color-focused work.

Critics and visitors to the exhibition were struck by the elegance and grace of Wilcox’s new works. The flowing lines, the sense of motion, and the subtle play of light and dark ink demonstrated that Wilcox had not lost her touch; if anything, she had gained a new depth in her art. The exhibition featured works that ranged from abstract representations of the human form, inspired by her memories and imagination, to more symbolic pieces, like the intricate ladder-like structures that seemed to reach upwards, perhaps symbolizing her own personal ascent out of darkness.

One of the standout pieces from the exhibition was a series of ink drawings that featured what appeared to be dancing figures, reminiscent of the works of Henri Matisse, a friend and influence from her earlier years in Paris. These drawings, characterized by their fluidity and sense of motion, seemed to capture the very essence of Wilcox’s struggle and triumph. The figures, although abstract, conveyed a sense of joy and liberation, as if the act of creation itself was a dance that Wilcox was leading.

Wilcox’s ability to draw upon her extensive knowledge of art history and her personal relationships with other artists, such as Willem de Kooning, who had himself experimented with blind drawing, lent an added layer of richness to the exhibition. It was not just a showcase of her latest works but also a reflection on her entire career and the ways in which she had been influenced by, and had influenced, the art world around her.

The Castelli exhibition was also significant in that it drew attention to the broader conversation about disability and creativity. Wilcox’s work challenged the notion that blindness or any other physical limitation should restrict an artist’s ability to create meaningful and impactful work. Her drawings were not just beautiful—they were a statement of defiance against the limitations imposed by her blindness.

Wilcox’s 1974 exhibition at the Castelli Gallery was a milestone in her career and a significant event in the art world. It showcased her remarkable ability to adapt and continue to produce powerful art despite the loss of her sight. The works presented in the exhibition were a testament to her resilience, creativity, and unyielding spirit. Wilcox’s journey from Beirut to Paris to Amagansett, and finally to this exhibition, was one of constant evolution, and her 1974 show at the Castelli Gallery remains a shining example of the triumph of the human spirit in the face of adversity.